How PyPack Trends Cost Effectively Queries 440TB of PyPI Data

There’s nothing more exhilarating than knowing one SQL query could end up costing you $2,750. But if you don’t like living on the edge, here are some techniques to help reduce your query costs.

BigQuery’s On-demand pricing model costs $6.25 per TiB, with the first TiB per month being free. I have been building PyPack Trends, a web app to compare Python package downloads inspired by npm trends. This app served as a learning exercise to explore web development.

A core part of this app is being able to cost-effectively serve the PyPI package downloads dataset. The dataset is made available on BigQuery for free, thanks to the Linehaul project. The downloads dataset alone is 440TB, which comes out to $2,750 if you run a simple select * from bigquery-public-data.pypi.file_downloads.

We can confirm this by either running a dry run query or if you’re using BigQuery studio, in the upper right-hand corner of the editor, it will display the estimated amount of bytes to be scanned if you run the query.

This is where understanding how the internals of your database can help you write cost-effective and performant queries.

One way to reduce the amount of data scanned is by selecting only the columns you need. BigQuery stores table data in a columnar format. This means when we select only one column, BigQuery will only scan that column’s worth of data. If I changed the query from doing a select * from bigquery-public-data.pypi.file_downloads to select project from bigquery-public-data.pypi.file_downloads this drops the data scanned from 440TB to 13.39TB which is $2,666 less.

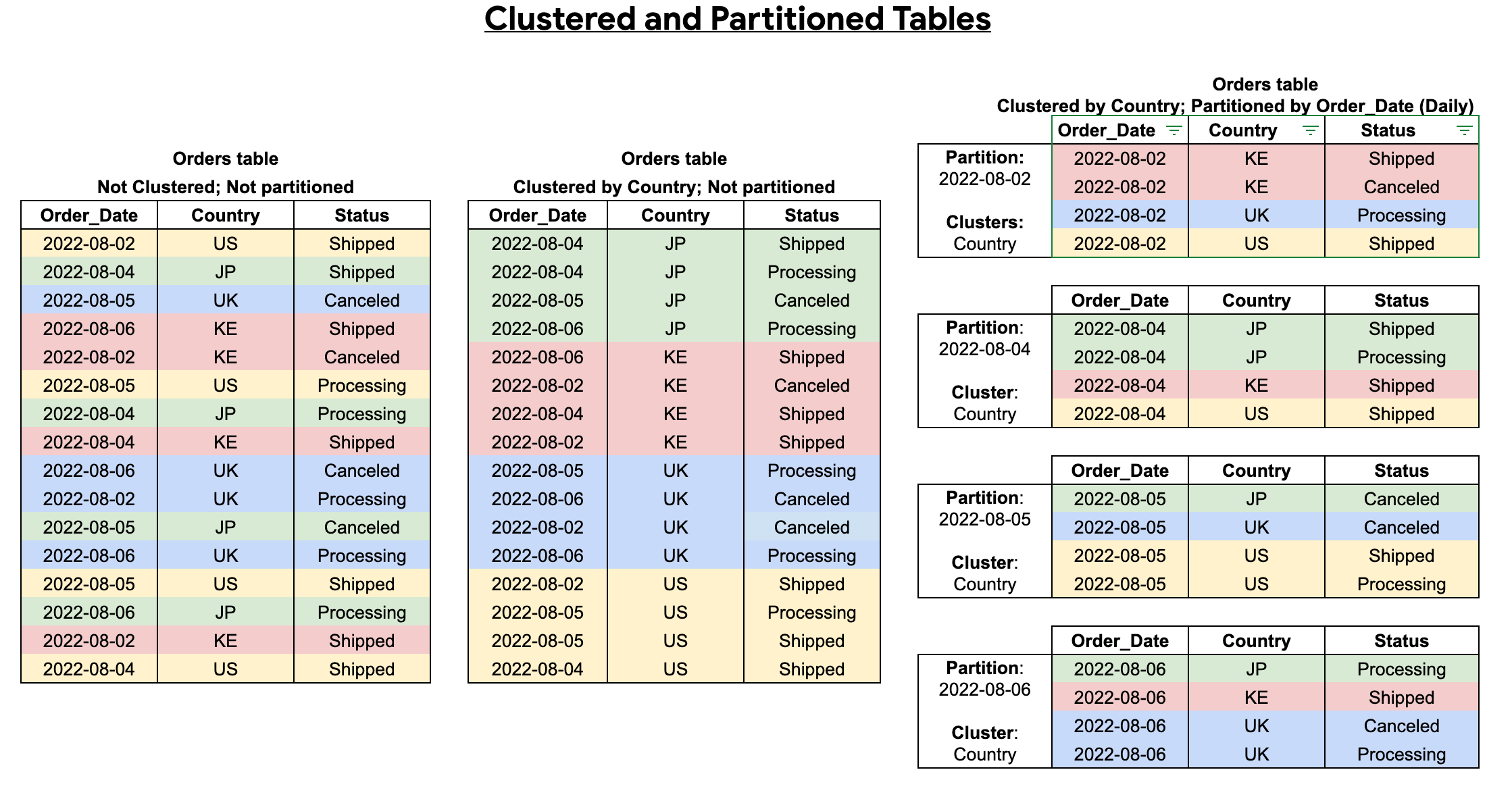

Another way to reduce the amount of data scanned is by taking advantage of partition pruning. A partitioned table divides the table into “chunks” called partitions. A standard column to partition on is typically a date column such as order_date, in our case, the PyPI file downloads table is partitioned on the timestamp column representing download time. This query will only scan 463.50 GB of data, select * from bigquery-public-data.pypi.file_downloads where timestamp_trunc(timestamp, day) = timestamp("2024-12-14").

While partitioning divides the data into smaller segments, clustering defines the table’s sort order. The formal definition from the BigQuery docs

A clustered column is a user-defined table property that sorts storage blocks based on the values in the clustered columns.

Like partition pruning, BigQuery will also prune these blocks when filtering on this column. Running the query select * from bigquery-public-data.pypi.file_downloads where project = 'duckdb' results in 762.27 GB scanned.

Columns commonly used for clustering are those frequently used in join operations. This image does a great job visualizing table partitioning and clustering:

Even with all these techniques implemented, BigQuery is not designed for frequent small-point queries targeting an individual row but rather large aggregate queries running across many rows. The terms to often describe these workloads are OLTP and OLAP.

Further optimization can be done by incrementally pre-aggregating the data and then exporting it to another more optimized database for OLTP workloads.

Daily download counts are too “nosiy” making it look like there are dramatic increases and decreases in daily downloads for a given package. To help smooth out the curve, I opted to pre-aggregate weekly per package.

Incremental processing is essential here because once we calculate one week’s download counts there should be no need to recompute that data again. To calculate the weekly downloads per project takes ~230 GB scanned. Ran 4 times a month would result in 80 GB shy of the free 1 TB per month. Perfect.

I prefer to use a tool like dbt to manage these queries, as it helps apply software engineering best practices to SQL code. Dbt even has a built-in incremental materialization method, which materializes as a table in your database and only transforms the data you tell dbt to filter for.

A best practice to help minimize the chance of running an expensive query is setting the maximum_bytes_billed in your dbt profile. Here is how I have configured my dev profile.

I have noticed that the BigQuery estimated bytes scanned can be overstated when running incremental models, so I have set it much higher than I would have liked here.

I have also developed a dbt macro called pypi_package_filter which checks the dbt target to see if it should filter for only a subset of packages. For the dev and ci targets I don’t need to be querying the full range of packages.

{% macro pypi_package_filter(column_name) -%}

{% set package_list = [

'dask',

'datafusion',

'duckdb',

'getdaft',

'ibis-framework',

'pandas',

'polars',

'pyspark'

] %}

{%- if target.name != 'prod' -%}

{{ column_name }} in ('{{ package_list | join("', '") }}')

{%- else -%}

true

{%- endif -%}

{% endmacro %}with

source as (

select * from {{ source('pypi', 'file_downloads') }}

),

renamed as (

select

timestamp as package_downloaded_at,

country_code as package_download_country_code,

url as package_download_url_path,

project as package_name,

file as package_download_file_details,

details as package_download_details,

tls_protocol as package_download_tls_protocol,

tls_cipher as package_download_tls_cipher

from

source

where

{{ pypi_package_filter('project') }}

)

select * from renamedLastly, I use dbt clone which takes advantage of BigQuery’s table clone feature.

A table clone is a lightweight, writable copy of another table (called the base table). You are only charged for storage of data in the table clone that differs from the base table, so initially there is no storage cost for a table clone. Other than the billing model for storage, and some additional metadata for the base table, a table clone is similar to a standard table—you can query it, make a copy of it, delete it, and so on.

This allows me to create a full copy of the expensive weekly downloads model into my own dev dataset at zero cost without having to recreate it from scratch. This feature requires access to the production dbt manifest JSON file, which fully represents your dbt project’s resources.

I run my dbt jobs through GitHub Actions and save the generated manifest file to my VPS ( I even have the dbt docs publicly available at dbtdocs.pypacktrends.com ). To retrieve the manifest file I rsync the files to my local machine.

After the data is pre-aggregated, I sync the data to an SQLite file on the VPS, essentially using SQLite as a read-only cache. I’m still experimenting with ways to relax SQLite settings to improve query performance, given the heavy read workload with infrequent writes ( once a week). Data reliability is also not a concern here as the source of truth is BigQuery, and I can always resync the data if I have to.

The downside of all this is that I no longer get the thrill when I run my queries. In tech, there are always tradeoffs.